Source: ForeignAffairs4

Source: The Conversation – UK – By Tony Kushner, James Parkes Professor of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations, University of Southampton

This article contains details of antisemitism and violence that some readers may find upsetting.

It’s evening at a remote Sussex pub in 1734 and a vicious triple murder has just taken place. Jacob Harris – a Jewish pedlar, smuggler and possible highwayman – stands accused of slitting the throats of the publican, his ill wife and a female servant.

I’ve studied the case for my latest book, The Jewish Pedlar: An Untold Criminal History. The point of interest for me was not whether Harris was guilty (he probably was). Or even whether – despite the seriousness of the crime – he was a victim of English antisemitism in everything from the newspaper coverage to the way he was later remembered. I was more interested in a series of questions about Harris’s background and motivations.

Harris had many aliases including Hirshal Hirsh and James Daves, reflecting both his criminal tendencies and complex identity that was both continental Jewish and very local. How on earth did someone of German-Jewish origin manage to integrate himself into the close-knit smuggling fraternity of Sussex?

What was Harris even doing in Ditchling Common, many decades before there was anything approximating to a Jewish community in Sussex? And what motivated him to commit the murders?

Despite the potential for prejudice against Jewish people at the time, I concluded that in the criminal world, as long as someone was trusted and useful, their background did not matter. It was only when Harris fell out with a fellow smuggler leading to a fatal fight that his life fell apart. The quandary for me as a social and cultural historian was how to write anything like a biography of Harris when there are no direct quotes from him in the surviving archive.

Completing my 340-page study therefore felt like somewhat of an achievement. To do so required intricate detective work (and indeed the advice of a real retired detective) to interrogate every piece of contemporary evidence.

This included the sparse legal record of the murders, the first Sussex assizes (court) record to be kept in the National Archives at Kew; a contemporary diary from a local landholder; and copious reports in British newspapers which “borrowed” heavily from one another.

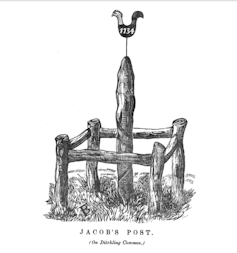

There was also a bill sent to the Treasury by the county of Sussex for the catching, imprisonment, trial, hanging and gibbeting of Harris (gibbeting involves placing a hanged body in a specially constructed iron cage at the scene of the crime). And there was a ballad which would have been written and sold at the gibbeting and has survived in various forms ever since.

Not one of these sources is straightforward, and this is also true of most of the authors and major players in contemporary responses to the murders.

The complexities of the case

Harris was not the only person in the case who had multiple names. There was also his first victim, the publican Richard Miles. His many names strongly suggest that he was on the wrong side of the law and almost certainly a fellow smuggler.

The lead justice of peace in the case, who later became an MP and major landowner, had also changed his name. As did the newspaper entrepreneur who was the only one who made explicit Harris’s Jewishness when reporting in his new title, Walker’s Weekly Post.

Even Sir Robert Eyre, the judge from London who sentenced Harris to be hanged and gibbeted, had a reputation for corruption, though I’m not saying it affected the decision in this case. I don’t doubt that Harris was guilty of the horrendous crimes he was charged with.

The gibbeted body

Having been found guilty in the county assizes at Horsham and hanged in that town, Harris’ body was then carted to the scene of the crime a good 15 miles away to be placed in the gibbet cage.

Author provided

A history of a local Sussex family compiled over many generations suggests that his skull remained in the cage some decades later. The post from which the gibbet cage was hung remained in position for much longer and soon became known as “Jacob’s Post”. Despite his crimes and his Jewish origins, he became a local folk hero.

To this day there is a heritage display on Ditchling Common to mark this momentous event in the district’s history.

Later Jewish criminals who were hanged became prized for their body parts by surgeons such as William Hunter (of the Hunterian museum in London) for racialised display. I didn’t want to treat Harris as this kind of object of study, but as a human being with family and friends (and no doubt enemies).

To discover more about Harris, his occupations and identity, I covered the period up to the second world war and followed Jewish pedlars and criminals in many different places from China to South America, from Sierra Leone to the Hebrides and from South Africa to the Caribbean. I also charted how the memory of Harris altered through time, from the Victorians who saw him as racially different and “naturally” criminal, through to a growing sensitivity towards his Jewishness in a post-Holocaust world.

It might be argued that at a time of growing hostility towards those of migrant origin and increasing racism, including antisemitism, what we don’t need now is a book on a Jewish criminal. I would argue that by trying to understand the individuality of these often remarkable – if often controversial – figures, it emphasises their fundamental humanity.

We cannot – and must not – expect any group of people to be perfect. As an asylum seeker (a former professional in Yemen) in an Essex hotel which has been subject to constant demonstrations in summer 2025 told The Guardian: “Yes, there are some refugees who do not behave respectfully or who do not follow the rules of the host society.” He added that this should not mean that all are regarded as such and that “every refugee has a story, and every human deserves dignity”.

In this respect in my book I certainly do not glorify Harris or downplay his crimes. I do, however, insist that he is not demonised as a “Jew murderer” as the Victorians would have it, and that see him instead as part and parcel of 18th century English rural life – a world far more diverse than we often assume.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

![]()

Tony Kushner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Why I had to become a murder detective for my book about an 18th-century Jewish pedlar – https://theconversation.com/why-i-had-to-become-a-murder-detective-for-my-book-about-an-18th-century-jewish-pedlar-262671