Source: ForeignAffairs4

Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Tamilla Triantoro, Associate Professor of Business Analytics and Information Systems, Quinnipiac University

Pick up an August 2025 issue of Vogue and you’ll come across an advertisement for the brand Guess featuring a stunning model. Yet tucked away in small print is a startling admission: She isn’t real. She was generated entirely by AI.

For decades, fashion images have been retouched. But this isn’t airbrushing a real person; it’s a “person” created from scratch, a digital composite of data points, engineered to appear as a beautiful woman.

The backlash to the Guess ad was swift. Veteran model Felicity Hayward called the move “lazy and cheap,” warning that it undermines years of work to promote diversity. After all, why hire models of different sizes, ages and ethnicities when a machine can generate a narrow, market-tested ideal of beauty on demand?

I study human-AI collaboration, and my work focuses on how AI influences decision-making, trust and human agency, all of which came into play during the Vogue controversy.

This new reality is not a cause for doom. However, now that it’s becoming much harder – if not impossible – to tell whether something is created by a human or a machine, it’s worth asking what’s gained and what’s lost from this technology. Most importantly, what does it say about what we truly value in art?

The forensic viewer and listener

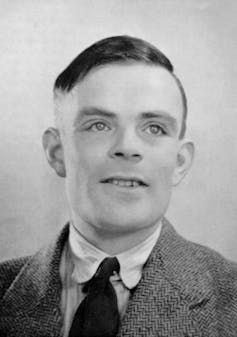

In 1950, computer scientist Alan Turing wondered whether a machine could exhibit intelligent behavior indistinguishable from that of a human.

He proposed his famous imitation game. In it, a human judges whether they’re conversing with a person or a computer. If the human can’t tell the difference, the computer passes the test.

Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

For decades, this remained a theoretical benchmark. But with the recent explosion of powerful chatbots, the original Turing Test for conversation has arguably been passed. This breakthrough raises a new question: If AI can master conversation, can it master art?

The evidence suggests it has already passed what might be called an “aesthetic Turing Test.”

AI can generate music, images and movies so convincingly that people struggle to distinguish them from human creations.

In music, platforms like Suno and Udio can produce original songs, complete with vocals and lyrics, in any imaginable genre in seconds. Some are so good they’ve gone viral. Meanwhile, photo-realistic images are equally deceptive. In 2023, millions believed that the fabricated photo of Pope Francis in a puffer jacket was real, a stunning example of AI’s power to create convincing fiction.

Why our brains are being fooled

So why are we falling for it?

First, AI has become an expert forger of human patterns. These models are trained on gigantic libraries of human-made art. They have analyzed more paintings, songs and photographs than any person ever could. These models may not have a soul, but they have learned the mathematical recipe for what we find beautiful or catchy.

Second, AI has bridged the uncanny valley. This is the term for the creepy feeling we get when something looks almost human but not quite – like a humanoid robot or a doll with vacant eyes.

That subtle sense of wrongness has been our built-in detector for fakes. But the latest AI is so sophisticated that it has climbed out of the valley. It no longer makes the small mistakes that trigger our alarm bells.

Finally, AI does not just copy reality; it creates a perfected version of it. The French philosopher Jean Baudrillard called this a simulacrum – a copy with no original.

The AI model in Vogue is the perfect example. She is not a picture of a real woman. She is a hyperreal ideal that no living person can compete with. Viewers don’t flag her as fake because she is, in a sense, more “perfect” than real.

The future of art in a synthetic world

When art is this easy to generate – and its origin this hard to verify – something precious risks being lost.

The German thinker Walter Benjamin once wrote about the “aura” of an original artwork – the sense of history and human touch that makes it special. A painting has an aura because you can see the brushstrokes; an old photograph has an aura because it captured a real moment in time.

AI-generated art has no such aura. It is infinitely reproducible, has no history, and lacks a human story. This is why, even when it is technically perfect, it can feel hollow.

When you become suspicious of a work’s origins, the act of listening to a song or viewing a photograph is no longer simply about feeling the rhythm or wondering what may have existed outside the frame. It also requires running a mental checklist, searching for the statistical ghost in the machine. And that moment of analytical doubt pulls viewers and listeners out of the work’s emotional world.

To me, the aesthetic Turing Test is not just about whether a machine can fool us; it’s a challenge that asks us to decide what we really want from art.

If a machine creates a song that brings a person to tears, does it matter that the machine felt nothing? Where does the meaning of art truly reside – in the mind of the creator or in the heart of the observer?

We have built a mirror that reflects our own creativity back at us, and now we must decide: Do we prefer perfection without humanity, or imperfection with meaning? Do we choose the flawless, disposable reflection, or the messy, fun house mirror of the human mind?

![]()

Tamilla Triantoro does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. AI has passed the aesthetic Turing Test − and it’s changing our relationship with art – https://theconversation.com/ai-has-passed-the-aesthetic-turing-test-and-its-changing-our-relationship-with-art-262997