Source: ForeignAffairs4

Source: The Conversation – UK – By Sudhansu Bala Das, Postdoctoral researcher in Linguistics, University of Galway

India is a home to numerous ancient and linguistically rich languages across its many regions. In a single home, a young person may speak, for example, Odia (the language spoken in the eastern state of Odisha) with their grandparents, switch to English for homework, and enjoy listening to Hindi songs on YouTube.

Far from being confusing, this coexistence is necessary and natural. It’s a hallmark of a nation where language diversity is embraced as a strength rather than being a barrier to be overcome.

India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, reflected this attitude in February this year when he remarked that there had “never been any animosity among Indian languages”. He was speaking at a major literary conference in the state of Maharashtra, where the vast majority of people, 84 million out of a population of 112 million, speak Marathi as a first language with Hindi a distant second.

“[Indian languages] have always influenced and enriched each other, he said. “It is our social responsibility to distance ourselves from such misconceptions and embrace and enrich all languages.” His remarks reinforced a broader message: that linguistic diversity is not a barrier, but a shared cultural strength that binds India together.

But language can also be a politically divisive issue in such a diverse country. And Modi and members of his government have been criticised for words and actions seen as trying to shape the use of Hindi, English and other languages within India. Because of the country’s linguistic complexity, the situation is always more complicated to navigate than it might first appear.

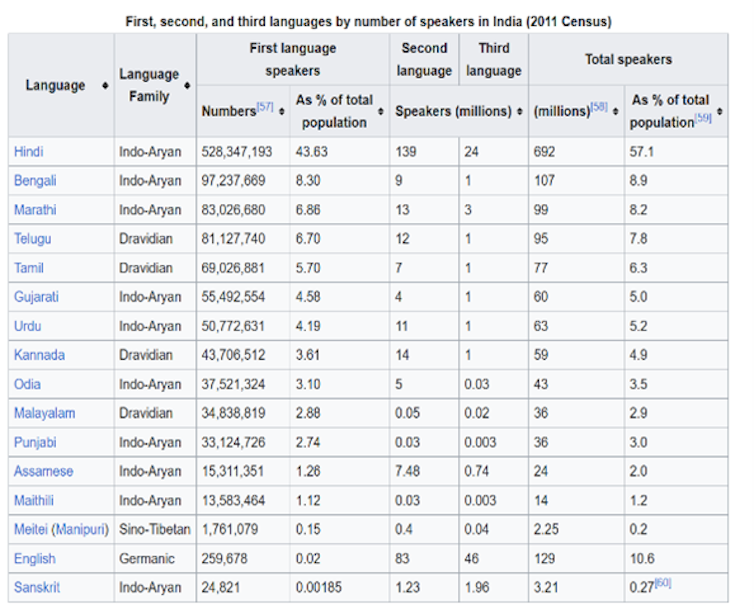

India has a total of around 19,500 languages or dialects that are spoken as mother tongues, according to the 2011 census. Of those, 22 languages are recognised as official under the Indian constitution.

The 2011 census found that 44% of Indians, about 528 million people, speak Hindi as their first language (meaning what is spoken at home). Similarly, around 57% of people use it as a second or third language.

That means Hindi has a broad presence across regions, but it exists alongside many other languages with equal value, including Marathi, Bengali (97 million), Telugu (81 million), Tamil (69 million) and Meitei (1.8 million).

2011 Indian census, CC BY-NC-SA

At the national level, India has two official languages: Hindi and English. Hindi is used for communication within the central government, while English is widely used in legal, administrative and international affairs. Each state can choose its own official language(s) for state-level governance. For example, Tamil Nadu uses Tamil, Maharashtra uses Marathi, and so on.

But in daily life, people often switch between languages depending on where they are and who they are speaking to, at home, at work, or in public spaces. According to the 2011 census, nearly one in four Indians said they could speak at least two languages, and over 7% said they could speak three.

India introduced a three-language formula in education the 1960s. This policy guideline encouraged students to learn three languages: their regional mother tongue, Hindi (if it is not already their first language) and English. This was intended to produce a flexible and inclusive approach across different states.

In 2020, the Modi government introduced a new national education policy that gave states more flexibility to pick which two Indian languages should be taught alongside English, but made the recommendation compulsory in all states. This has led to a backlash in several states because some fear it effectively introduces Hindi teaching by the backdoor and will dilute the use of other languages.

There is also considerable debate in India about the role of English, which about 10.6% of Indians speak to some degree but some believe is a relic of colonial rule. Modi himself has suggested this is the case and has taken action to reduce the official use of English, for example in medical schools.

However, he has also acknowledged the importance of English, particularly in global communication, and spoken of the value all Indian languages bring to the country’s unity and progress. “It is our duty to embrace all languages,” he told the audience in Maharashtra, adding that Indian languages, including English, “have always enriched each other and formed the foundation of our unity”.

Many see the language as a link between the many linguistic communities of India. Others see it is a tool for social mobility, especially for lower castes. Some have even accused the government of wanting to discourage English in order to maintain social privileges and promote the dominance of Hindi.

On the other hand, the 2020 national education policy mandates the teaching of English. It recommends bilingual textbooks in English and local languages, and that English should be taught “wherever possible” alongside mother tongues in primary education.

The government is also taking steps to make the digital world more inclusive to people, whatever their language. Launched by Modi in 2022, the Bhashini project is a national AI initiative supporting speech-to-text, real-time translation and digital accessibility in all 22 official languages. This aims to make digital platforms and public services more inclusive, especially for rural and remote communities.

As poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore once wrote: “If God had so wished, he would have made all Indians speak with one language … the unity of India has been and shall always be a unity in diversity.”

In India, children today grow up speaking their mother tongue, with many learning Hindi to communicate across regions, and gaining English skills for global connections. India’s future does not depend on choosing one language over another, but on enabling them to flourish side by side.

There’s a Chinese proverb: “To learn a language is to have one more window from which to look at the world.” With thousands of such windows, India’s future is rooted in both unity and diversity.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

![]()

Sudhansu Bala Das does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Many tongues, one people: the debate over linguistic diversity in India – https://theconversation.com/many-tongues-one-people-the-debate-over-linguistic-diversity-in-india-261308