Source: ForeignAffairs4

Source: The Conversation – UK – By Sevrine Sailley, Senior Scientist, Marine Ecosystem Modelling, Plymouth Marine Laboratory

Climate change is reshaping fish habitats. Some fish are winners, others are losing out.

Fish already face plenty of pressure from overfishing and pollution. Climate change is adding more: warmer waters and shifting food supplies cause what’s known as a predator-prey mismatch. This means prey and predator are not in the same place at the same time, which not only affects our diets but also fishing industries and ocean health more widely.

As the ocean heats up, fish try to stay in the conditions they’re best suited to. Some species will move, but others can’t relocate so easily – for example, if they need to live in a certain habitat at a particular life-stage, such as in kelp that offers shelter for breeding. So, depending on the species and location, climate change could create new fishing opportunities for some countries, and big losses for others.

Fisheries managers typically group fish into “stocks”. These are populations of the same species in a defined region, often based on national borders. But those human-made boundaries don’t matter to fish. As they shift in response to climate change, managing their populations will become more complex and will need to be flexible and responsive.

By 2050, waters around the UK are expected to warm by about 1°C if we follow a “moderate” emissions path. If emissions continue to rise unchecked, the increase could reach 2-3°C by the end of the century. At the same time, the food that fish eat (such as tiny plankton) could drop by as much as 30%.

My team and I used advanced computer modelling to predict how 17 key commercial species such as mackerel, cod, plaice, tuna and sardines might respond to two future climate scenarios. Our results show a patchwork of winners and losers.

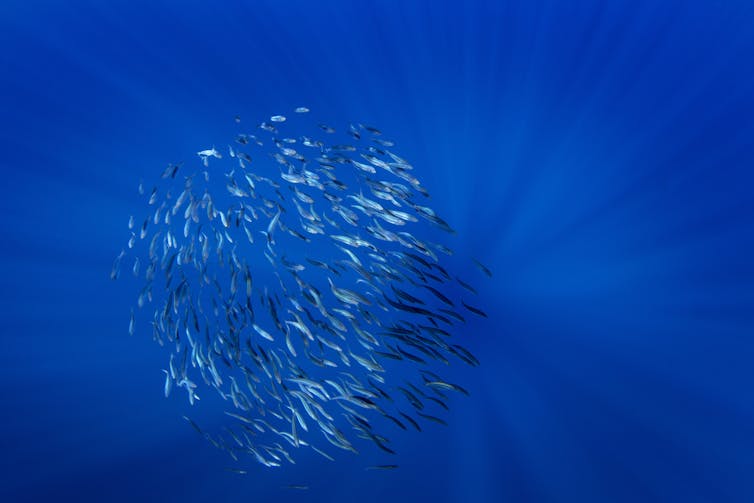

Martin Prochazkacz/Shutterstock, CC BY-NC-ND

Take sardines and mackerel. These species live in the upper ocean and are sensitive to temperature. Both are expected to shift northward. This shift would be around 20 miles in the North Sea and up to 80 miles in the north-east Atlantic by 2100 under a moderate emissions scenario.

While sardines may thrive, with a 10% boost in Atlantic abundance, our model suggests mackerel could decline by 10% in the Atlantic and 20% in the North Sea. Consequently, the type and quantity of fish available will change.

Warm-water species like bluefin tuna may benefit within UK waters. Tuna is projected to shift only slightly (by approximately 4 miles) under the same scenario, but their abundance could rise by 10%, potentially bringing more of them into UK waters. That’s good news for fishers already targeting this high-value catch, or those looking to change their main target species.

But bottom-dwelling species like cod and saithe (pollock) face a tougher future. These fish prefer colder, deeper waters and have fewer options to escape warming seas due to depth limitations.

In the North Sea, they’re projected to shift southward by around 9 miles because that’s where the remaining cool, deep water is. But this won’t be enough to avoid a significant decline in their numbers: their populations are expected to drop by 10-15% under a moderate scenario by 2050.

Do the seasons feel increasingly weird to you? You’re not alone. Climate change is distorting nature’s calendar, causing plants to flower early and animals to emerge at the wrong time.

This article is part of a series, Wild Seasons, on how the seasons are changing and what they may eventually look like.

Changing tides

And if climate change accelerates, the declines become far more severe. By the end of the century, North Sea cod and saithe could fall by 30-40%, according to our model. Mackerel abundance could drop by 25% in the Atlantic, while sardines might see only a modest 5% increase, despite moving 155 miles northward. Bluefin tuna could see a 40% rise in numbers, shifting 27 miles further north.

We’ve estimated how species will shift their locations – but computer models can’t account for every interaction between marine species. For example, predator-prey relationships can be crucial in shaping an ecosystem. Bluefin tuna is a predatory species which hunts shoals of herring, mackerel and other fish.

Other predators including dolphins, seals and seabirds will all be influenced differently by climate change, with varying responses in terms of eating their favourite fish snacks.

Our projections also don’t account for continued fishing pressure – for example, 24% of north-east Atlantic fisheries are not sustainable. Further overfishing will compound the strain on fish populations.

To keep stocks healthy, fishery managers need to start planning for these changes now by factoring climate into their stock assessments. Industry regulators will also need to reconsider who gets to fish where as species move.

Fish don’t carry passports. Their shifting habitats will challenge longstanding fishing agreements and quotas. Nations that once relied on particular species might lose access. Others may find new, unexpected opportunities.

With smart management and serious action on climate, seafood can thrive in the future. Doing nothing now isn’t an option — unless we want familiar favourites like cod to vanish from our plates.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Sevrine Sailley receives funding from UKRI and Horizon Europe.

– ref. How climate change is making Europe’s fish move to new waters – https://theconversation.com/how-climate-change-is-making-europes-fish-move-to-new-waters-254650