Source: ForeignAffairs4

Source: The Conversation – UK – By Nicolas Forsans, Professor of Management and Co-director of the Centre for Latin American & Caribbean Studies, University of Essex

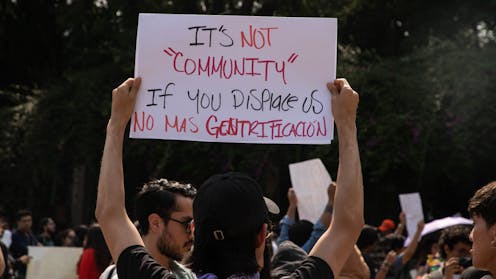

When thousands of residents took to the streets of Mexico City in July chanting “Gringo, go home”, news headlines were quick to blame digital nomads and expats. The story seemed simple: tech-savvy remote workers move in, rents go up and locals get priced out.

But that’s not the whole tale. While digital migration has undeniably accelerated housing pressures in Latin America, the forces driving resentment towards gentrification there run far deeper. The recent protests are symptoms of several structural issues that have long shaped inequality in the region’s cities.

Long before digital nomad visas became policy buzzwords after the pandemic, Latin America’s cities were changing at speed. In 1950, around 40% of the region’s population was urban. This figure had increased to 70% by 1990.

Nowadays, about 80% of people live in bustling cities, making Latin America the world’s most urbanised region. And by 2050, cities are expected to host 90% of the region’s population. Such rapid urbanisation has proved a magnet for international investors, tourists and, more recently, digital nomads.

In Latin America, gentrification has often involved large-scale redevelopment and high-rise construction, driven by state policies that prioritise economic growth and city branding over social inclusion.

Governments have re-branded entire working-class or marginalised areas as “innovation corridors” or “creative districts”, as in the La Boca neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, to attract investment. Neighbourhood re-branding has fostered resentment among locals and, in Buenos Aires, policies supporting self-managed social housing.

The introduction of integrated urban public transport systems has, while improving city access for marginalised communities, also triggered property speculation in once-isolated communities. In the Colombian city of Medellín, for instance, this has driven up prices and displaced long-time residents from hillside neighbourhoods like Comuna 13.

This is not an isolated case. A study from 2024 found that transport projects in Latin America are frequently leveraged by governments to attract private investment, effectively using mobility as a tool for urban restructuring rather than social equity.

Alexander Canas Arango / Shutterstock

Researchers call the urban development seen in Latin America “touristification”. This is a form of extractivism where – just like raw materials are removed from the earth for export – urban heritage, culture and everyday life are “mined” for economic value.

In the Barranco district of the Peruvian capital, Lima, heritage is marketed for tourism. But while the district’s bohemian and artistic identity has become a distinctive tourism asset, Barranco now faces challenges that threaten its sociocultural diversity and authenticity. The price of land there increased by 22% between 2014 and 2017, compared with just 4% in San Insidro, which is considered the wealthiest district of metropolitan Lima.

In Chile, the designation of Valparaíso’s historic quarter as a Unesco world heritage site in 2003 led to an increase in heritage-led tourism. Persistent outward migration of long-term residents from the city centre has led to a severe decline in the residential function of the world heritage area – and with it, the loss of vibrant local life.

Symptoms of deeper issues

Protests against high rents and displacement in Latin America are often framed as direct responses to gentrification. However, academic research and policy analysis suggest these protests are symptoms of much deeper structural issues.

Latin America is one of the most unequal regions in the world. Limited access to things like quality education and formal employment means many urban residents are already vulnerable before gentrification pressures begin. More than half of the current generation’s inequality in Latin America is inherited from the past, with estimates ranging from 44% to 63% depending on the country and measure used.

Cities in the region also have long histories of spatial and social segregation, with marginalised groups concentrated in under-resourced neighbourhoods. Gentrification often exacerbates this by pushing these populations further to the periphery.

Cartagena, a port city with roots in colonial-era divisions, possibly exemplifies the greatest urban segregation in Colombia’s history. Spaniards and other Europeans lived in the fortified centre, while enslaved people were confined to poorer neighbourhoods like Getsemaní outside the walls.

Recently, urban planning decisions have been taken there that favour certain groups over others. Only the colonial legacy linked to Europeans has been protected. Getsemaní, once populated with slaves’ homes and workshops, is now home to luxury hotels, restaurants and housing.

Nowaczyk / Shutterstock

Finally, a large share of Latin America’s urban workforce is employed informally. Informality, where workers lack job security and social protections, is not just an unfortunate effect of economic development. It is an integral part of how global capitalism and urbanisation unfold in Latin America.

It reflects the failure of state and market systems to meet the needs of the majority. Rising rents and living costs driven by gentrification disproportionately hurt those who have few resources to absorb such shocks.

Protesters in Mexico aren’t just angry at an influx of remote workers sipping flat whites. They are responding to decades of urban inequality, neglect and exclusion. What is emerging is a continent-wide battle over who gets to live in, profit from and shape the future of Latin American cities.

The region’s urban future doesn’t have to mirror its past. But getting there means moving beyond simplistic narratives about foreign renters or digital workers, and tackling the structural issues that have long shaped inequality in Latin America’s cities.

![]()

Nicolas Forsans does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Mexico’s tourism protests are a symptom of longstanding inequality in Latin American cities – https://theconversation.com/mexicos-tourism-protests-are-a-symptom-of-longstanding-inequality-in-latin-american-cities-261634